Not So Much Ice, Ice Baby Anymore - The South And North Pole

The Malizia Explorer is spending this winter in the Antarctic, partaking in 3 different research missions in this so-called “last-wilderness”. However, whilst this vast icy region remains mostly untouched, our actions have well and truly made an impact on these environments already, even if just from a far.

The Arctic Ocean, the northernmost region of our planet, is, depending on the season, covered by approximately 7 to 15 million square kilometres of sea ice. On land, the cold Arctic climate houses large ice masses in glaciers and keeps the ground frozen in permafrost (split the word up and you will quickly understand what permafrost is: the ground is in a state of permanent frost, with all organic material, soils and sediments completely frozen). The Antarctic on the other side of the globe is of equal importance, acting as Earth’s largest freshwater storage by holding 60% of the world's total fresh water frozen as ice.

Albedo Effect

The poles play a crucial role in the global climate system due to the ice's ability to reflect sunlight, a phenomenon closely tied to the albedo effect. Ice caps have an albedo higher than 80%, meaning they reflect about 80% of solar radiation and only absorb 20%, therefore preventing significant heat absorption.

However, as temperatures rise, the sea ice with a high albedo begins to melt and darker surfaces like seawater become exposed. Having a lower albedo than light surfaces, they reflect less sunlight, leading to a higher absorption of heat by the Ocean.

This transition from white ice to dark seawater represents a feedback loop known as the ice-albedo effect, contributing to the ‘polar amplification’ of global warming in the Arctic and Antarctic. As a result, the poles are warming three to four times faster than the rest of the planet, which in turn accelerates the melting of ice caps furthermore - it’s a vicious circle! Current projections suggest that the Arctic could be seasonally ice-free as early as 2030.

The effects of this feedback loop have cascading consequences that are felt globally. In both the Arctic and Antarctic, amplified warming accelerates the melting of ice sheets, contributing to sea level rise. Communities and wildlife in distant regions are not spared: rising sea levels place additional stress on marine and coastal ecosystems, disrupt wildlife, threaten infrastructure, and lead to economic hardships, displacement of communities and loss of livelihoods in coastal areas.

The melting ice is also reshaping ecosystems. As ice sheets melt and temperatures rise, previously ice-covered surfaces are being exposed, creating opportunities for new life while also threatening established ecosystems. A recent article in the renowned science journal Nature showed that certain regions of the Antarctic continent are becoming ice-free and beginning to green over as moss covers the landscape. Beneath the moss, a layer of soil is forming, offering an environment for species that typically would not thrive on the Antarctic Peninsula. However, these "invasive species" are not always welcome, as they may negatively impact the existing flora and fauna. Animals that have adapted to the harsh conditions over centuries could struggle to compete with newcomers in the future.

Greenhouse Gasses, Permafrost and Ocean Acidification

As temperatures rise, the thawing of permafrost - permanently frozen ground - releases carbon dioxide and methane, which have been trapped in organic matter for thousands of years. This adds to the already elevated levels of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. It creates a feedback loop similar to the albedo effect: rising greenhouse gases warm the planet, melting permafrost, which in turn releases more greenhouse gases, further accelerating the cycle.

The Ocean plays a crucial role as a carbon sink, absorbing CO2 from the atmosphere and striving to reach a state of equilibrium. This means that as CO2 levels rise in the atmosphere, the Ocean absorbs more carbon accordingly, acting as a temporary buffer for climate change. However, this increased carbon uptake comes with a consequence: Ocean acidification.

Colder waters, such as those in the polar regions, are more likely to absorb carbon dioxide than warmer waters, making them more susceptible to Ocean acidification. A simple real-life example to visualise this is a fizzy drink in summer versus one in winter. In winter, the colder temperatures allow you to keep an open drink outside for much longer before it goes flat, whereas in summer, it loses its fizz much faster.

If we extend this example and imagine adding a piece of chalk to the fizzy drink, we can expect it to start fizzing and gradually dissolve. This is similar to what’s happening to many marine organisms in the Ocean. As the Ocean becomes more acidic, the skeletons of organisms made of carbonate minerals, like those of corals and shellfish, begin to corrode and dissolve. This poses a significant threat to the entire marine food web. Tiny organisms, like the pteropod (a sea snail), are particularly affected by Ocean acidification. Since these organisms are crucial at the base of the marine food chain, any disruption in their population can have profound impacts on larger species higher up the food chain.

Taking Action Is Key

Anthropogenic effects however are not limited to below sea level: In 1985, researchers discovered an abnormality in the ozone layer above the Antarctic - an ozone hole. Ozone is a clear, chemically active gas that absorbs ultraviolet B light, a harmful component of sunlight. The ozone layer, which surrounds the planet, protects us from this dangerous radiation. The formation of the ozone hole was primarily driven by the use of chlorine and bromine, found in CFCs used in coolants, aerosols and refrigerators, along with the favourable meteorological conditions in the Antarctic.

However, this environmental crisis also shows that it is possible to reverse human impacts. In response to the ozone hole, the Montreal Protocol was agreed upon, aiming to phase out ozone-depleting chemicals. Thanks to this international agreement, the ozone hole is now recovering - a hopeful reminder that positive change is possible when global action is taken.

Recognising the pivotal role that polar regions play in regulating the planet’s climate and supporting biodiversity, several conservation programmes have been established to safeguard these fragile ecosystems.

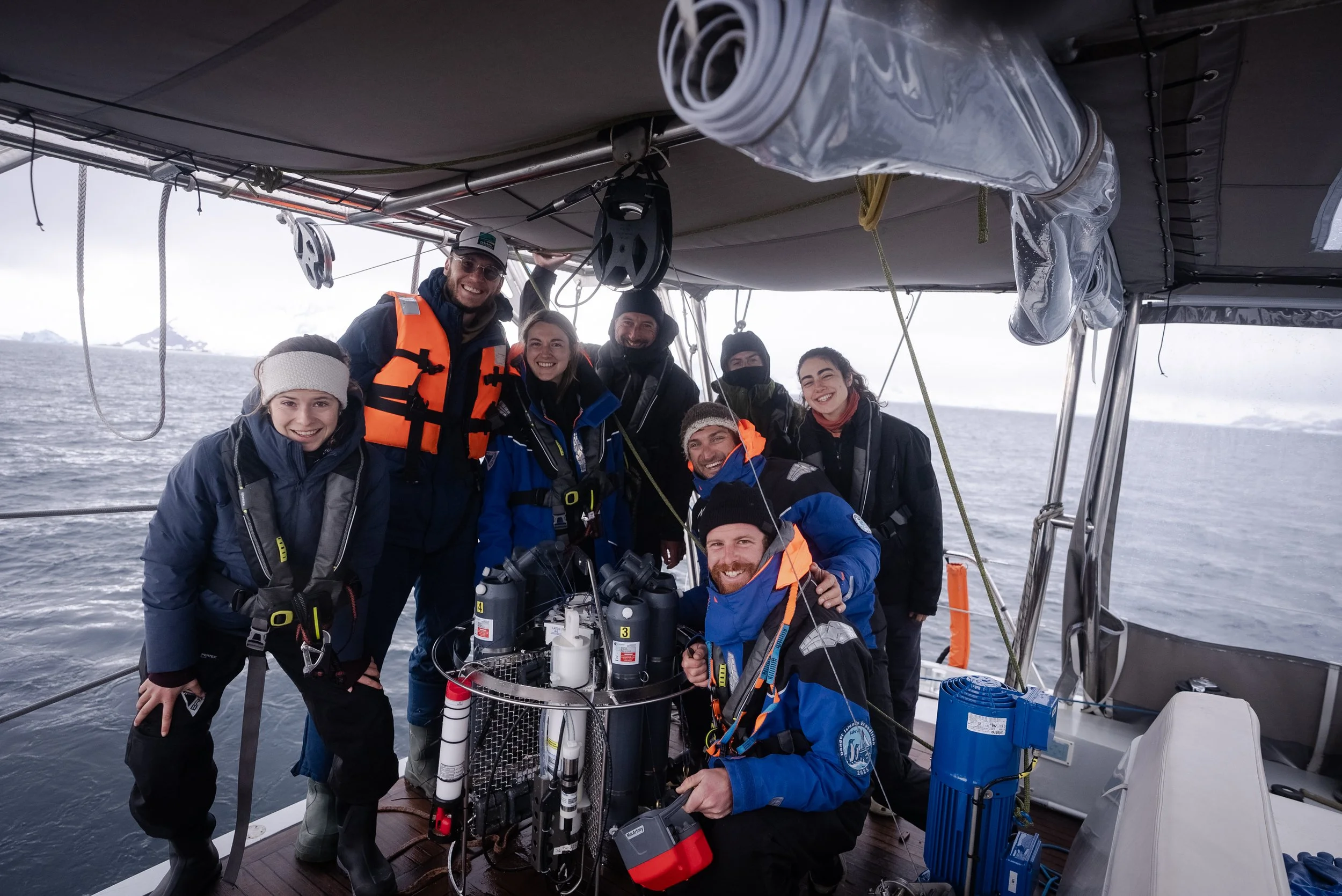

If you have been following Team Malizia and our activities, you may know that our main field of work revolves around sailing across the Ocean at top speeds aboard IMOCA sailing yachts in offshore races. As a team, we have been able to 3 separate lines of data lapping the planet and mapping CO2, temperature and salinity levels from remote regions, critical for scientists to understand the development of our Ocean and climate change. To however go that extra mile further, with the launching of our research vessel, which is wholly dedicated to science and science communication, the Malizia Explorer science vessel takes us not only “by chance” (like during offshore races) to regions worth exploring, but specifically to environments in desperate need of studying. That is why, after one successful mission at the end of 2025, where we worked closely with the Environmental Agency, Alfred-Wegener-Institute and ThINK Jena, our current joint mission has taken us to the Antarctic peninsula again, where we are supporting a scientific mission with Under The Pole.