Science at the polar front

After setting sail on the 7th of January 2026, the crew onboard the Malizia Explorer headed south, the bow of the vessel pointed toward the Western Antarctic Peninsula. While some team members were still tucked away below deck, recovering from their first days of finding their sea legs, Dr. Lea Olivier from the Alfred Wegener Institute was keeping a close watch on the horizon. She was looking for fog, which often accompanies the “Antarctic Convergence” and signals the transition into polar waters.

To reach Antarctica from Ushuaia, Argentina, one must cross the Drake Passage, the body of water connecting the southernmost tip of South America with the South Shetland Islands of Antarctica. Known as one of the roughest seas in the world, the Drake is hardly the gentlest introduction to a month-long sailing expedition, especially for those unaccustomed to a constantly moving deck beneath their feet.

Yet this time, the crew was spared the Drake’s notorious fury. Instead of the feared “Drake Shake,” they encountered what sailors affectionately call the “Drake Lake.”

“It’s quite incredible to see the Ocean like this,” said first-time Antarctica voyager and German climate activist Luisa Neubauer on day three of the journey. “Sometimes the water and the waves remind me a little of a toddler. One moment the world goes under, and the next it’s all happy sunshine, like nothing ever happened.”

For Léa Olivier, a French post-doctoral researcher in Oceanography who’s been working closely with Team Malizia for many years, however, these waters were familiar territory. As a climate scientist at the Alfred Wegener Institute, she has participated in numerous Antarctic expeditions. Just last year, she spent three entire months aboard the German research icebreaker Polarstern.

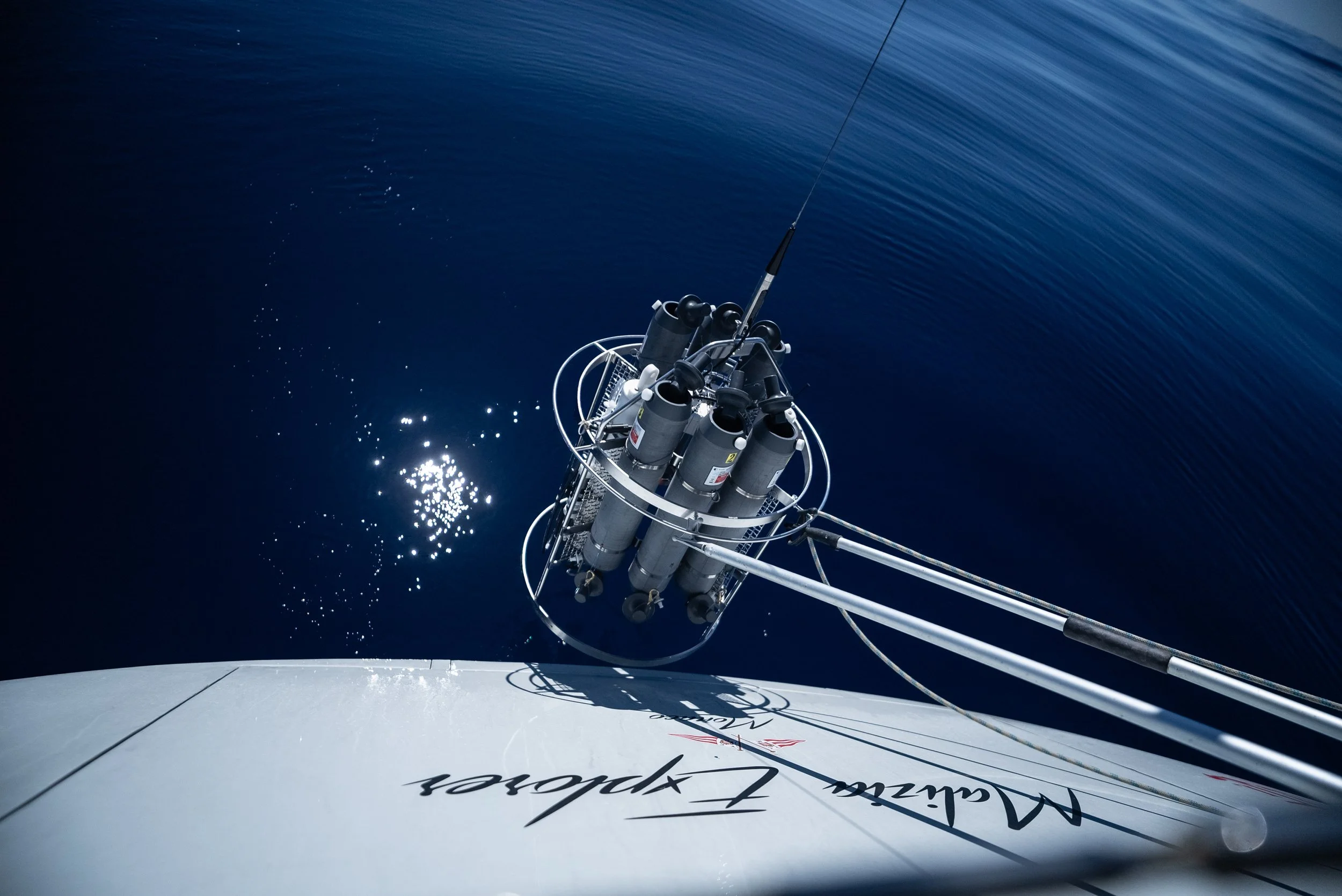

Dr. Lea Olivier operating the CTD Rosette © Marin Le Roux / PolaRYSE / Team Malizia

On this mission, Léa’s scientific focus lies on specific regions of the Southern Ocean where changes in sea-ice cover, Ocean stratification, and glacial melt strongly influence water-mass distribution and carbon fluxes. In practical terms, this involves deploying a CTD rosette, an instrument capable of diving to great depths, collecting water samples, and measuring the physical and chemical properties of seawater at different levels (conductivity, temperature, and density, therefore the name “CTD”). The Western Antarctic Peninsula is one of the fastest-changing regions on Earth, playing a key role in global air-sea CO₂ exchange and future climate dynamics. And as data from the Southern Ocean remains surprisingly scarce, it is critically important to continue to study this region and close research gaps.

The Drake Passage itself is not only a bridge between two continents, but also a meeting point of two different oceanic water masses. Here, cold, dense Antarctic waters from the south collide with warmer, subtropical waters from the north. This boundary is known as the Antarctic Convergence.

The CTD system consists of sensors and a rosette equipped with six Niskin bottles for water sampling. Lowered from the stern of the ship by a mechanical winch, it can reach depths of up to 400 meters. The sensors transmit real-time data on conductivity (salinity), temperature, and depth throughout the water column. At selected depths, the bottles are closed to collect water samples, which scientists later filter, preserve, and analyze in laboratories to determine parameters such as carbon content, DNA, or pollutants.

Encircling the Antarctic continent, the Antarctic Convergence shifts its latitude with the seasons. One common indicator of its location is the fog that often blankets these waters. Because the water masses on either side of this polar front differ significantly in their physical properties, the region is an interesting subject for scientific measurements, making this the first place that the Malizia Explorer conducted its CTD rosette deployments - one north of the convergence and one south of it.

After completing both CTD casts, Lea reviewed the data and explained, “We can already see how the water is changing as we get closer to the continent.”

Not long after, the crew began spotting breaching whales and soaring albatrosses. Soon, the first icebergs and islands appeared on the horizon, which is a clear sign that their destination was nearing.

Their first stop was the Melchior Islands, a low-lying archipelago that offers natural shelter. It was here that Under The Pole, co-leads of the “Global Warming” mission, were waiting to finally join forces in person. Shortly before 6 a.m. local time, Under The Pole made contact with the Malizia Explorer via VHF radio, and shortly after welcomed the crew.

This moment marked the official starting shot of their joint Antarctic mission.