First Steps on the Danger Islands: Reaching One of Antarctica’s Most Remote Frontiers

For months, our team had been preparing for the moment the Malizia Explorer would make landfall on the Danger Islands, which are seven small islands spanning just 5 km² off the Antarctic Peninsula. It’s a place recently designated as an Antarctic Specially Protected Area (ASPA 180), and, following Germany’s commitment to protect it, a team of scientists and the Malizia Explorer crew set sail towards these untouched islands. On the 19th of November 2025, the crew of 14, composed of scientists, media representatives, sailors, and a cook, made their way to the end of the world on the 26-metre sailing vessel to study penguins and seven small yet ecologically valuable islands.

Their dual mission: gathering data on this newly protected area on land, and collecting evidence that may support the expansion of the protected zone into the marine environment if necessary.

After days of navigating ice, waiting out weather systems, and analysing shifting satellite data every few hours, the team finally reached the outer edge of the archipelago. What followed was a mixture of scientific achievement, difficult decisions, and the humbling reminder that Antarctica is always in charge.

“Kids, you are witnessing a very special moment right now. We’ve just got the Danger Islands in sight,” said Boris Herrmann, sailor and explorer, on Thursday morning during a live Antarctic school lesson streamed to 120 students in Kiel, Germany. While this might have sounded casual, it was monumental - up until that minute, the whole crew had doubted this arrival. But let’s start at the beginning.

Crossing Into Antarctica’s Wildest Waters

After leaving Ushuaia, Argentina, considered the gateway to Antarctica, the crew was ready for great challenges ahead: rough seas, waves as high as two story houses and grey stormy skies. What they encountered, however, were calm seas, sunshine, and only a little swell. Uncharacteristic of this region. “Like the Med, but cold,” someone remarked.

After five days of sailing, the first stop was King George Island, seeking shelter in Maxwell Bay. Here, nine permanent research stations stand elevated on stilts to withstand snow and wind. The feeling of solitude and untouched landmasses hadn’t reached the crew yet when arriving on this research hub, but this was after all only the first holding point; a safe place to wait for a weather window before continuing to Joinville Island, west of the Danger Islands and 20 hours away.

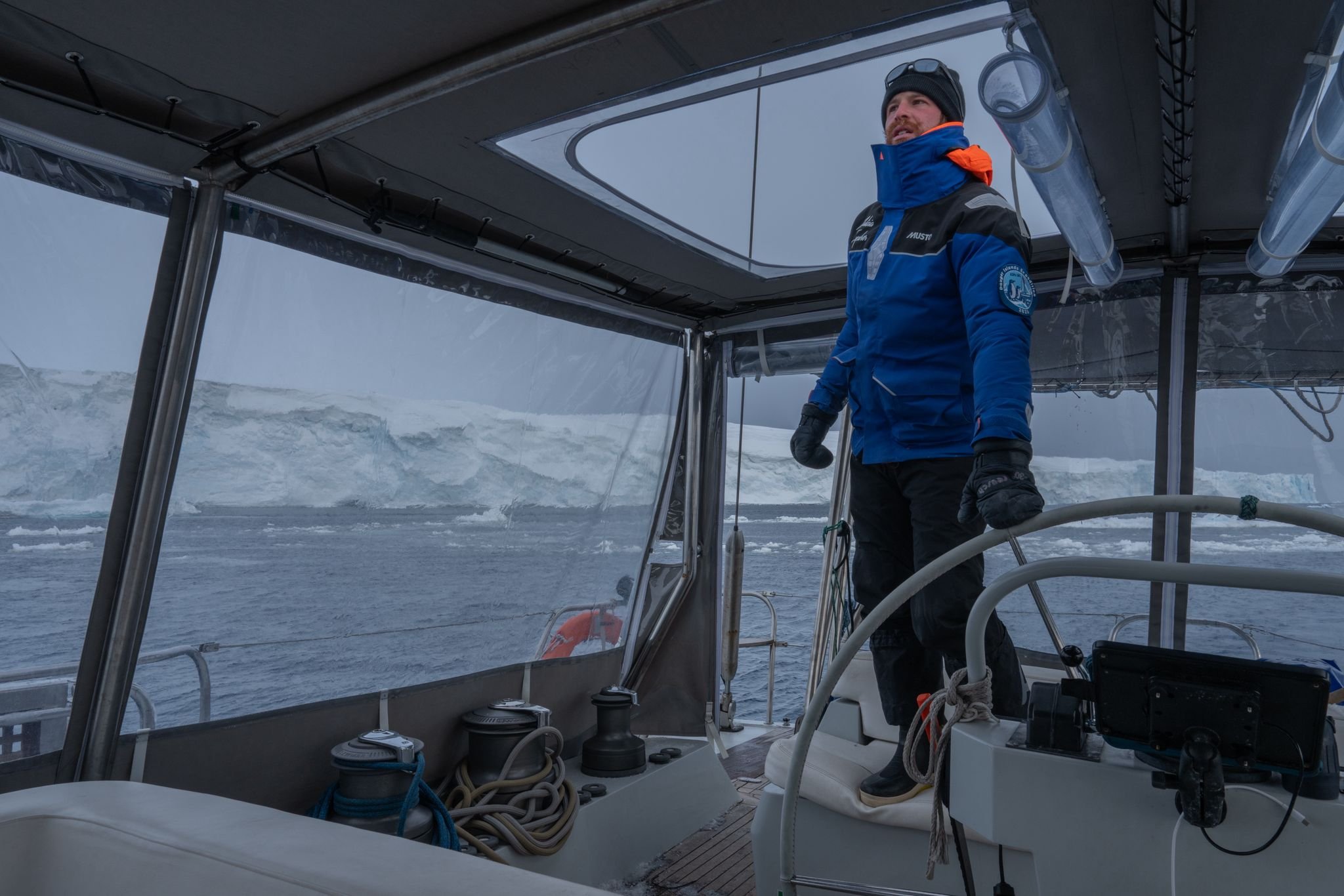

This second holding point gave the crew their first true sense of Antarctic isolation. The landscape felt untouched, exposed, and vast. This was the first real moment where the continent felt impossibly remote. From here, every eight hours the crew pieced together new satellite images, reports from two nearby ships, and their own observations to understand how the ice was moving and when a safe passage to the Danger Islands might open.

In Antarctica, conditions change by the hour. Wind, currents, and temperature can shift ice fields completely and a clear passage can close in minutes. Before even setting sail, scientists, media crew, and sailors had agreed: as desperately as they wanted to reach the Danger Islands, it might simply not be possible.

However, watching the images, weather, and an ambivalent forecast, the team decided at 9 p.m. on Wednesday the 26th of November that their chances were as good as they would get, and they would attempt the journey into the archipelago.

Reaching Brash Island

What followed was a slow, cautious overnight passage along the coast, weaving through growing fields of “pancake ice”, which are thin ice discs that freeze together into impassable sheets. Large icebergs were easy to avoid, visible from afar in the Antarctic summer’s light and towering over the dark sea like white giants. But the smaller, chest-freezer-sized blocks were the real danger. Step by step, the team edged forward, with one sailor positioned on the mast spreaders to watch the water ahead and call instructions through the night.

Time passed slowly, however by sunrise, the crew spotted birds, and the Danger Islands faintly appeared in the distance. This however was not the time to celebrate, as the closer the boat approached, the less likely arrival seemed to feel… And yet, to the entire team’s surprise, they made it. → cut to Boris Herrmann excitedly exclaiming the Malizia Explorer’s arrival during the Antarctic livestreamed school lesson we mentioned before!

They reached Brash Island, a tiny landmass barely 1 km long at 11am in the morning. Unfortunately, where birds nest, so do their excrements, so this island, which is home to around 100.000 penguins layering the islands was olfactorily detectable from afar. The smell of the massive colony carried across the water even before the team stepped ashore.

Equipped with 40kg of scientific equipment each and a weather change looming, everyone got straight to work. The rule was simple: work until you can no longer work.

Starting at 11 a.m., right upon arrival, the teams split into three main tasks: mapping the islands, sampling and tagging penguins, and conducting biodiversity surveys.

Mapping the Islands

The scientific team from ThINK, led by Osama Mustafa, carried out drone mapping. In addition to close-range drone flights, a fixed-wing drone flew pre-programmed survey routes over every island in the archipelago, sometimes more than 10 km away. It photographed each island in detail and returned to be recharged before flying the next mission.

This was a breakthrough: high-quality imagery of all seven islands captured in a single day, which is something that had never been achieved before.

Penguin Tracking for Marine Protection

Researchers from the Alfred Wegener Institute focused on catching Adélie penguins. This sampling takes less than 1 minute to do and entails taking swabs from their mouths and cloaca, and collecting blood samples to test for signs of diseases such as bird flu. In addition, they equipped selected penguins with tiny trackers that will naturally fall off after about three months. These devices and the tracks they document will reveal where the penguins forage, which is essential information for determining how far a potential ASPA 180 marine protected area would need to extend to protect both penguins and their feeding grounds.

Additionally, sixteen slightly incubated eggs were collected to analyse for occurrence of persistent chemicals and pollutants accumulated globally or released by melting glaciers.

Biodiversity Surveys

Another group documented vegetation, mosses, lichens, and invertebrates. Fun and interesting fact you may never have thought about: the largest land living animal on the Danger Islands is the Wingless Midge (A reminder: penguins do not actually live there, but spend most of their lives in the water!)

It was an enormous amount of work compressed into a single, precious weather window. Had the team not been called back by the crew of sailors watching the winds shift earlier than forecast from south to east, pushing ice towards the islands, they would have worked well beyond the 11 hours they already had.

Quickling packing up their equipment, the scientists left the islands and headed back to the sailing vessel.Scrambling back onboard the team said their goodbyes to the islands in passing, as if they waited too long, they would risk becoming trapped.

The Long Exit

What followed was one of the most demanding navigations of the expedition: hour after hour searching for safe passages. Some as wide as a football field, some opening briefly before closing again. The Antarctic summer light, never fully dark, helped the team trace patterns in the ice and inch forward. Four-hour shifts required absolute focus. The boat, after all, is no icebreaker. Small victories, like a narrow passage discovered, were celebrated, but the fear of the next passage being closed remained.

By early morning, the boat reached more open water. Icebergs still dotted the horizon, but the team could finally breathe again.

What We Achieved and What Comes Next

Although the original goal was to land on all seven islands, Antarctic conditions made that impossible. But the mission’s most important scientific objectives were achieved.

After a short rest at Joinville Island, where the team were sheltered from swell but still battered by strong winds, the crew sailed back to King George Island. There they now wait. A second attempt to land on the Danger Islands will only happen if a clear multi-day weather and ice window appears - and at the moment, the forecast suggests the opposite. Safety remains the absolute priority.

Even if they cannot return, the team agrees this achievement alone represents meaningful scientific progress.

You can only manage what you measure, and you can only detect change if you have a baseline. The scientific teams have already collected a substantial amount of data from the Danger Islands, and the first penguin tracking signals are already coming in, ready for comparison with predictive models.

For now, the crew remains anchored off King George Island, watching the weather. If no window appears by Wednesday, they will return to Ushuaia, bringing home an unprecedented wealth of knowledge about these previously unstudied islands.